Tough on terrorism, tough on the causes of terrorism?

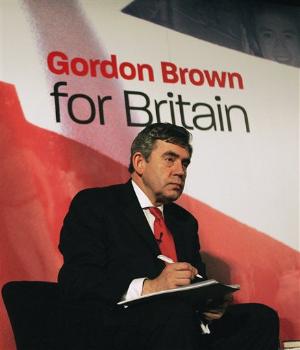

For the second weekend running, the papers were full of just what our glorious government is going to do to tackle the "ever growing" terrorist threat. While a week previously Tony Blair went out of his way to prove just how little he cares or even understands civil liberties, with John Reid continuing to do his "we're all doomed" act, alongside the irredeemable suggestion that the "sus" laws could be reintroduced, Gordon Brown tried his best to position himself both as a defender of our current rights, while still being "tough" on terrorism. You could almost call it his tough on terror, tough on the causes of terror moment.

For the second weekend running, the papers were full of just what our glorious government is going to do to tackle the "ever growing" terrorist threat. While a week previously Tony Blair went out of his way to prove just how little he cares or even understands civil liberties, with John Reid continuing to do his "we're all doomed" act, alongside the irredeemable suggestion that the "sus" laws could be reintroduced, Gordon Brown tried his best to position himself both as a defender of our current rights, while still being "tough" on terrorism. You could almost call it his tough on terror, tough on the causes of terror moment. Regardless of his pledge to defend our ancient liberties, which should be welcomed when Blair, Reid and Blunkett all repeatedly rode roughshod over them in their pusillanimity in the face of the tabloid shrieks, his plans need close analysis.

Top of the list was the Sun-appeasing measure to increase the maximum detention period for "terrorist suspects" to 90 days. This wasn't much of a surprise; Brown has long supported the idea, mentioning a number of times how he thinks it's needed. The difference is that Brown has promised that he will increase the judicial oversight involved, although how this would work in practice hasn't been set out. The police already have to go to a judge every week and set out where they are in their investigation so that the continued detention of a suspect is rubber stamped, and the concern has to be that although judges have so far held the police to account well, ordering at least one suspect to be released because it was clear they had no evidence which justified his continued incarceration, that they can't always be depended on to do so, increasing the chances that if the legislation was OK'ed that we could have the prospect of innocent men or women being locked up for three months, something guaranteed to breed alienation, cynicism and further mistrust in the police and security services.

It may well be true that a majority of the public supports such a lengthy time period, as polls suggested last time round. Despite the failures of Forest Gate and the ricin plot that never was trial, most are still prepared to give the police and government the benefit of the doubt when they make clear they believe such legislation is needed. 90 days has however rightly became a civil liberties cause célèbre; it's the defining mark of a government that has already treated civil liberties as something to be abandoned rather than strengthened, ridiculed and undermined rather than respected, going too far. The reality is that 28 days has only been needed in its entirety once since it becoming law, and many of us suspected the police may have being doing so only to make a point. The argument is that it's either needed because of the information coming from abroad involved in building a case, or that encrypted documents on hard drives take time to be broken. As Liberty has pointed out, there already exists a law where you can be charged and prosecuted for refusing to disclose a decryption key, something which is yet to be used. As for the abroad argument, this seems more like a delaying tactic for the police's own lack of resources to deal with such cases: that should never be used as an excuse to hold someone for longer than necessary. 90 days needs to vigorously resisted.

Many of us have long been calling for intercept evidence to be made admissible, and Brown does genuinely seems to have listened. While Reid may have been toying with the idea, only to reject it, Brown has at least suggested that the privy council should hold a review into how it could be introduced. While this is an excellent step forward, Craig Murray provides some sobering inside knowledge which might yet spoil the party:

So the proposal being considered by the Home Office is this – that the defence should not be allowed access to all the material from wiretaps of the accused. The prosecution would have to disclose in full only the conversation, or conversations, being directly quoted from. The security services are prepared to go along with that, and the Home Office believe that the public demand for wiretap evidence to be admissible will drown out any protests from lawyers. We will be told the Security Services are not staffed to cope with fuller disclosure.

You read it here first. As my friend put it: "You see, in the minds of the Home Office, justice equals more convictions."

If accurate, this could well be the equivalent of legions of dodgy dossiers being produced in court as evidence against "terrorist suspects". Intelligence is nuanced, frayed and often inaccurate; it's when you start taking out the caveats, Alastair Campbell-style, and present it as definitive that the problems start, as we know all too well. The one benefit, even if such a discriminatory measure went ahead, would be that we'd at least finally find out exactly what those currently held under control orders are accused of, something which even they have never been informed of. Certainly a case of hoping Brown gives the go-ahead for the review, and then waiting to see what they come up with.

The other high-profile proposal is for the police to be given the power to continue to question and interrogate suspects after they have been charged, something which is at the moment strictly verboten. The attraction is that this might well negate the need for a further extension to 28 days detention without charge, but at the moment it seems to be positioned as another addition rather than a substitution. The exact details of what would be permitted, how long a suspect could be additionally questioned, and other relevant safeguards against potential abuse need to clearly defined and set out, as otherwise this could be far more dangerous than even 90 days without charge would be. Brown is again apparently setting out judicial oversight for the measure, which would need to be even more rigorous than that reviewing the continued detention of a suspect. The possibilities of a suspect being browbeaten into confessions by constant questioning and otherwise are stark: without a clear set of guidelines and like the 90 day proposal, a yearly review by an independent parliamentary committee or individual, it should be rejected.

"Lesser" new initiatives announced by Brown were a suggestion to make terrorism an "aggravating" factor in sentencing, like crimes that are racially motivated are. The obvious problem with that is the very definition of "terrorism", and whether legitimate protests could again be stigmatised as result, as they have been under Section 44 and the protection from harassment legislation, and as Rachel points out, conspiracy should already be able to cover it. It seems more an attempt to lengthen sentences of those who might be prosecuted for being on the outer edges of plots, involved in fraud or funding, when the law should be enough as it is, with judges' being able to use their discretion.

Brown also apparently wants to give MPs and peers greater powers to scrutinise the work of the security services, toughening up the Intelligence and Security Committee by letting MPs rather than the prime minister elect its members and ensuring that the heads of MI5 and 6 have to give evidence in public, ending the disgrace of Eliza Manningham-Buller refusing to appear before the Human Rights Committee without a reason why, even though its meeting would have been in secret. This is a decent first step, but it really doesn't go far enough: on July the 6th 2005, Manningham-Buller apparently told MPs that the terror threat was under control. Within a year and six months, the threat that had been under control had ballooned into 30 plots, 200 active terrorist groups or networks, and 1600 individuals either plotting or facilitating attacks, here or abroad. The obvious question then is, was MI5 hopeless prior to 7/7, or have they been burnt by downplaying and instead decided to exaggerate as a better option? We'll most likely never know for sure, but this just proves the need for either a watchdog similar to the Independent Police Complaints Commission for 5 and 6, or for an independent commissioner modeled on something like the information commissioner, whom would have full access to both agencies. This would likely be heavily resisted, but as the poll of 500 Muslims commissioned for Channel 4 demonstrates, we may well need such a measure for trust and faith to be restored.

There's plenty there that's easy to disagree with, but with the exception of the insistence of 90 days needing to be reintroduced, there's nothing that should be rejected out of hand. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats now need to as much as those of us dedicated to defending civil liberties hold Brown to what he says, and thoroughly overview any new anti-terror proposals. We need to hope that Brown is able to resist the worst excesses of the Scum in demanding ever tougher new laws, as it was instrumental in scuppering any chance that Charles Clarke had of reaching a consensus over his original plans in the aftermath of 7/7. Blair then declared that the rules of the game had changed. Brown can prove they have by remembering that it's governments and draconian, illiberal laws that are the real threat to the public, not murdering terrorists who can be effectively contained by the legislation we already have.

Labels: 90 days, civil liberties, Gordon Brown, terror

Post a Comment