Cold war syndrome.

It's difficult to know exactly how to respond to the decision to expel 4 Russian diplomats over the refusal of Moscow to extradite Andrei Lugovoi. At first look, it seems both to be by no means a harsh enough display of displeasure, considering how a British citizen was murdered in cold blood using elements which could have only have been obtained by going through government channels, yet also a pointless gesture for gesture's sake, making it even less likely that any sort of deal could possibly be reached.

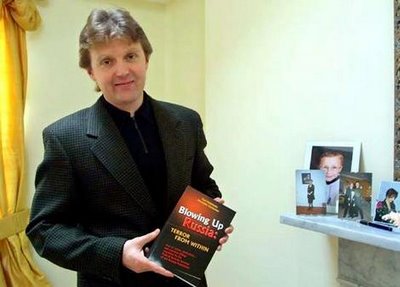

It's difficult to know exactly how to respond to the decision to expel 4 Russian diplomats over the refusal of Moscow to extradite Andrei Lugovoi. At first look, it seems both to be by no means a harsh enough display of displeasure, considering how a British citizen was murdered in cold blood using elements which could have only have been obtained by going through government channels, yet also a pointless gesture for gesture's sake, making it even less likely that any sort of deal could possibly be reached. There's so much murk surrounding the whole case that it's almost impossible to come to any firm conclusions about anything involving it. What we do know is that Litvinenko is not the only critic of the Kremlin under Putin to die in highly suspicious circumstances, nor is it likely that he will be the last. The question ultimately is whether the decision to murder him went right to the top, whether it was taken by underlings, or even by those simply associated or formerly connected to the FSB/KGB who now consider any dissent about the course which the new Russia has taken as treachery to be responded to with deadly force.

If we are to connect the dots between the two most high profile individuals to be assassinated, Litvinenko and Anna Politkovskaya, the motive may become slightly clearer, but not by much. Both Litvinenko and Politkovskaya had made damaging, highly controversial contentions, in the former's case concerning the 1999 Russian apartment bombings, which started the second brutal war in Chechnya and quickly elevated Putin to president, and in Politkovskaya's case her continual exposes of the abuses on the ground in that other poor, benighted country. Litvinenko accused the FSB of being behind the bombings, a false flag operation which, if true, most certainly served its purpose. While Politkovskaya concentrated more on the situation that those bombings brought about, she wasn't immune from entering the same kind of conspiracy ground that Litvinenko did; she conducted an interview in the aftermath of the Moscow theatre siege with a Chechen FSB agent, Khanpash Terkibaev, who she considered to have been the real kingpin of the hostage taking, arranging for them to make the journey to Moscow, with the promise that he would also arrange for them to get out afterwards. Just to further set the mind racing, a file which Litvinenko gave to Sergei Yushenkov containing his own allegations and suspicions was eventually passed to Politkovskaya. Every single character in this whole pass-the-parcel game is now dead: Yushenkov was assassinated just days after his return from visiting Litvinenko. Terkibaev died in a car accident in Chechnya.

In additional to all the conspiracy theorising, we have to consider the money aspect. Litvinenko had become good friends with Boris Berezovsky, the oligarch that managed to get away, at least for now. Much of Putin's popularity lies with his continuing attempts to cut the alleged robber barons who made their money buying and selling formerly state controlled assets at what are now considered prices well below their actual worth down to size. Considering how the vast majority of Russian people suffered, at least in the short term, during the "experiments" in extreme neo-liberalism conducted in the early 1990s, and how the country itself has only now just about recovered, we always ought to keep in mind the fact that Berezovsky is himself wanted in Moscow on fraud and political corruption charges. While it's unlikely that he could get a fair trial in the current climate, we should always keep open the possibility that the charges against him are credible, whatever we think about Putin and the FSB's antics. This then raises the question of why Litvinenko, and not Berezovsky, who is much more of a substantive threat to Putin than Litvinenko was, who could be dismissed as a conspiracy nut especially considering some of his later accusations, was not the target himself. It might well be that Litvinenko's murder was a warning that if he kept up his campaigning, and potential funding of what Putin fears most - a velvet revolution - that he would be next. If this was the objective, then it has backfired spectacularly, as we have since seen.

A lot of commentators have one basic problem with Russia: they see it instantly through the prism of the cold war, as if the Soviet Union never went away. As understandable as this is, especially considering how Russia has started to once again exercise its long-resting might, it misses the point that Russia is now more isolated than it has ever been. The money might be flooding in because of its reserves of natural resources, but on most policy matters it has never felt so alone. While once it even seemed likely that Russia could eventually join the EU, it now finds itself as a pariah once again. This is not entirely through its own actions, as bad as its human rights abuses and drift away from democracy have been: the rise of the neo-conservatives in Washington, with one of Bush's first acts being to tear up the anti-ballistic missile treaty, and now with the prospect of having missile interceptors in Poland, supposedly aimed at Iran and North Korea when anyone with even half a braincell realises they're directed at Russia, has been just as influential. The West has treated Russia since the collapse of communism as a subjugated nation, never to be allowed to rise again. That it appears to be attempting to do so is as much a reason for some of the opprobrium it's received as its own repression of political opposition has been.

Where does this all leave us? What is our response to Russia's own inevitable reaction? Rather than exchanging tit-for-tat diplomatic blows, our answer has to be more subtle. An increase in funding of democratic organisations, NGOs which Putin has desperately banned more out of paranoia than anything else, is certainly one step. Another has to be an attempt to be seen as an honest broker: rather than being 100% behind the decision of the US to place new bases in Poland and the Czech Republic, we have to consider Russia's own legitimate grievance, and attempt to reach a compromise. What Putin and his successor will fear the most is the Russian citizenry themselves: we have to empower them against their own autocrats, not against us.

Labels: Alexander Litvinenko, Russia, Russian diplomat expulsion, Vladimir Putin

Post a Comment