More unanswered questions for the BBFC over Last House on the Left.

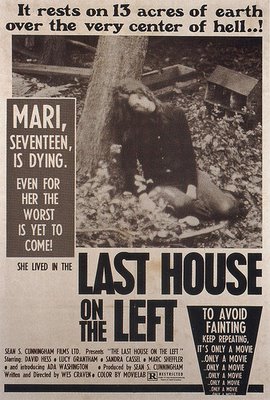

Just to keep everyone on their toes and make it as difficult as humanly possible to predict what the British Board of Film Classification's next move on its guidelines, if any, is going to be, especially in light of its decision to ban Murder Set Pieces and to finally give Manhunt 2 an 18 after the Video Appeals Committee forced it into seeing sense, Last House on the Left, Wes Craven's first and most notorious film, has finally been passed completely uncut for the first time ever in the UK.

Just to keep everyone on their toes and make it as difficult as humanly possible to predict what the British Board of Film Classification's next move on its guidelines, if any, is going to be, especially in light of its decision to ban Murder Set Pieces and to finally give Manhunt 2 an 18 after the Video Appeals Committee forced it into seeing sense, Last House on the Left, Wes Craven's first and most notorious film, has finally been passed completely uncut for the first time ever in the UK.Notable not only because it was Craven's first film in a career which continues to this day and has included the Hills Have Eyes, the Nightmare on Elm Street series and the Scream series, but also because of its long and chequered censorship history, Last House on the Left was one of the few films on the eventual "video nasties" list drawn up by the director of public prosecutions that had never been given any sort of certificate in this country, alongside such other luminaries as Cannibal Holocaust (now available, but heavily cut), House on the Edge of the Park (same) and Gestapo's Last Orgy (still "banned", although considering SS Experiment Camp's uncut passing, could well get through if submitted).

Initially rejected when it was submitted back in 1974, and then rejected again for a cinema run in 2000, it was again rejected, this time on Video/DVD in 2001. Surprisingly, less than six months later it was finally passed by the BBFC on the same format, albeit with 31 seconds of cuts. The BBFC's justification was:

Cuts required to humiliation of woman forced to urinate, violent stabbing assault on woman and removal of her entrails, and woman's chest carved with a knife. Cuts required under the Video Recordings Act 1984 and BBFC Classification Guidelines

Blue Underground, the submitter at the time, challenged the cuts with an appeal to the VAC, noting that far from the BBFC's justification being that it was making cuts to the sexual violence, as outlined in the BBFC's guidelines, it was in fact cuts to the violence within the film. Indeed, the rape scene, which is far from explicit, is contained intact. Unlike in the case of Manhunt 2, the VAC didn't agree, and upheld the BBFC's cuts. Blue Underground therefore decided not to release it, and Anchor Bay instead acquired the rights and submitted a pre-cut version that was subsequently passed uncut.

The question therefore has to be what has changed between July 2002 and March 2008. The answer is very little. The BBFC's guidelines were updated in 2005 in line with a larger survey, but there were no real changes over violence or sexual violence. The only conclusion that can be reached is that the BBFC realised that it had overstepped the mark back in 2002, perhaps mindful of how only two years' earlier the film had still been completely rejected. The swift move from banned to completely uncut isn't entirely unprecedented: a late film by Lucio Fulci, probably best known for the "video nasty" Zombie Flesh-Eaters, the Cat in the Brain was banned in 1999 and then given an uncut 18 just four years later, albeit under a different title. The history of films that had either been banned, or because they appeared on the "video nasty" list, subsequently felt unsuitable to be passed only shortly after the panic had calmed down, is often of having piecemeal cuts made, then when time has further passed, for the film to be subsequently released uncut. Zombie Flesh-Eaters itself was one of those that suffered this slow death of a thousand cuts, re-released in 1992 and 1996 with heavy cuts, subsequently submitted again in 1999 and cut by only 23s, and then finally passed completely uncut in 2005.

Even this isn't really an entirely satisfactory answer. One half of the BBFC's justification for cutting Last House on the Left was the Video Recordings Act of 1984, which certainly hasn't changed since 2002. Nor though has the BBFC's classification guidelines on sexual violence, or at least not openly. It's hard not to think that one of Craven's own arguments, that his film had been unjustly persecuted, is close to being the actual truth. The other obvious question is where this leaves the BBFC to go. The sexual violence in a film such as Murder Set Pieces is apparently enough to warrant its rejection, but the Last House on the Left, which just 6 years ago according to the BBFC's own student website "eroticised sexual violence" and the cutting of which provided a "robust endorsement of the BBFC's strict policy on sexual violence" is now tame enough to be released onto the public without fear of anyone getting a hard-on. The answer then is where it's always been: in a place where if it needs to it can justify almost anything it does, reasonably safe in the knowledge that it can usually get away it, and if not, a few years down the line the mores and attitudes will have moved on. It might make a mockery of their own guidelines and attempts at openness, but as it long as it keeps the wolf from the door which is the entire removal of its authority to cut and ban at will, most people, and certainly the BBFC itself, will stay happy.

Labels: BBFC, censorship, Last House on the Left, moral panics, video nasties, Wes Craven

Post a Comment